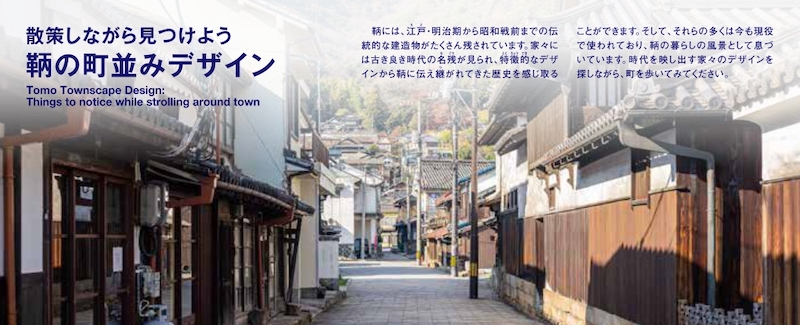

Corner sign

Buildings packed with artisanry

An Inheritance of Craftsmanship

In Tomo, a longstanding and common practice has been to break down old buildings and re-purpose their materials in the construction of newer buildings.

Including this method of re-purposing old building materials, a number of different, traditional techniques have been used in historical buildings in Tomo.

Restoration and Repair of Historic Buildings

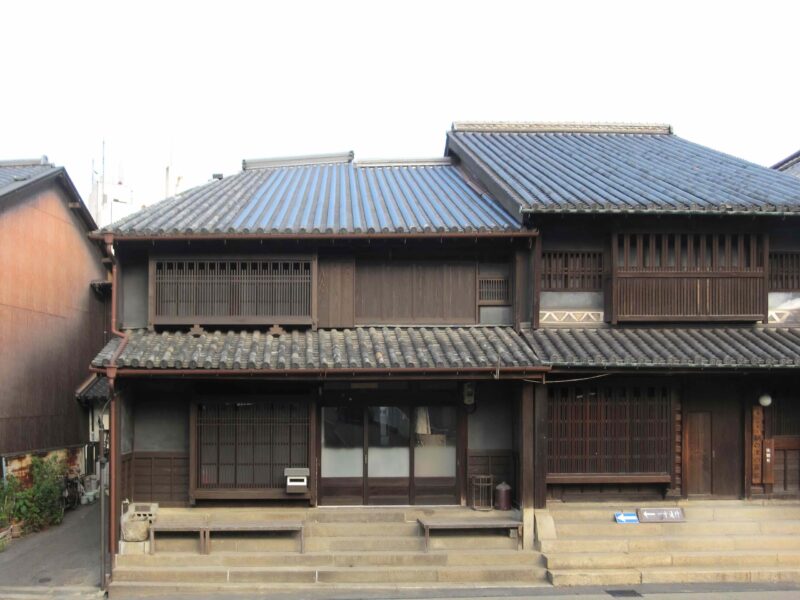

Many of the historic buildings in Tomo have been rebuilt, added to and re-purposed multiple times since their original construction. The building that you are currently in is a restored town house thought to have been constructed during the early Meiji period. The restoration process involved examining the workmanship of the remaining pillars, beams and other materials, studying how wind and rain have deteriorated the building and then, from this, confirming what the original structure looked like while undertaking construction to reproduce it.

A technique unique to Tomo

A fitting method unique to Tomo was used for the pillars of this building. This fitting method involves joining two pieces together in the axial direction. Given that this fitting was done with pillars of almost exactly the same length, it is thought that in Tomo, where maritime shipping was a well-developed industry, the transport of lumber of a standardized length has been a common practice here since long ago.

Repair and restoration process

The wood, tiles and other materials from a building provide a number of valuable clues for determining how and when the building was constructed, and, from these, a variety of techniques are utilized to restore and repair the building using the original materials as much as possible. In the case of this building, no staining or coloration was applied to the new building materials or the mended sections of the original materials, thus making it easy to see which sections were repaired.

See if you can identify which sections have been repaired.

Wood Fitting Experience

Please return the materials to their original locations when you are finished.

大工

Carpentry Techniques

A variety of techniques were used in constructing the buildings in Tomo in order to not waste wood. These techniques include “hagiki,” which is used for removing and mending the decayed sections of wood with new material, “netsugi,” which is used when the base of a pillar is damaged, and “umeki,” which is used when filling in holes in old wood.

Netsugi

The bases of the pillars in a traditional building are set atop the building’s stone foundation, which is close to the surface of the ground and which makes them more susceptible to water and termite damage. Because replacing the entire pillar is a waste of material, the netsugi technique is used to replace only those parts of the pillar base which are damaged. Also, a technique known as “hikari-tsuke” is used to create a better fit between the bottom of the pillar and the uneven surface of the stone foundation so that the pillar and the stone foundation will be connected as snugly as possible.

Hagiki

This is a technique for repairing damaged or decayed sections identified in the sides of pillars, beams and other wooden materials by removing those sections and affixing new material to them. When affixing the new materials, the same species of tree is used and the wood grain is aligned in order to integrate it with the original material while keeping as much of the old wood intact as possible.

Umeki

When reusing old wood, there may be holes in the wood left over from the last time it was worked. The umeki technique is used to reduce the visibility of such noticeable spots by filling them in with the same type of material and aligning the wood grain. When performing ukemi and other spot repair techniques, the newly added material will shrink over time. In anticipation of this, the new material is purposely worked so that it is approximately 3mm larger than the original material it is replacing.

左官

Plastering Techniques

Earthen walls used in traditional buildings can be roughly divided into two categories: “shinkabe,” in which the space between the pillars is filled with earth and covered over while leaving the surface of the pillars exposed, and “okabe,” in which both the space between the pillars and the pillars themselves are covered. Because the pillars are covered over in earth in okabe walls, they are comparatively more fire resistant than shinkabe walls and were, therefore, commonly used for storehouses and other such buildings.

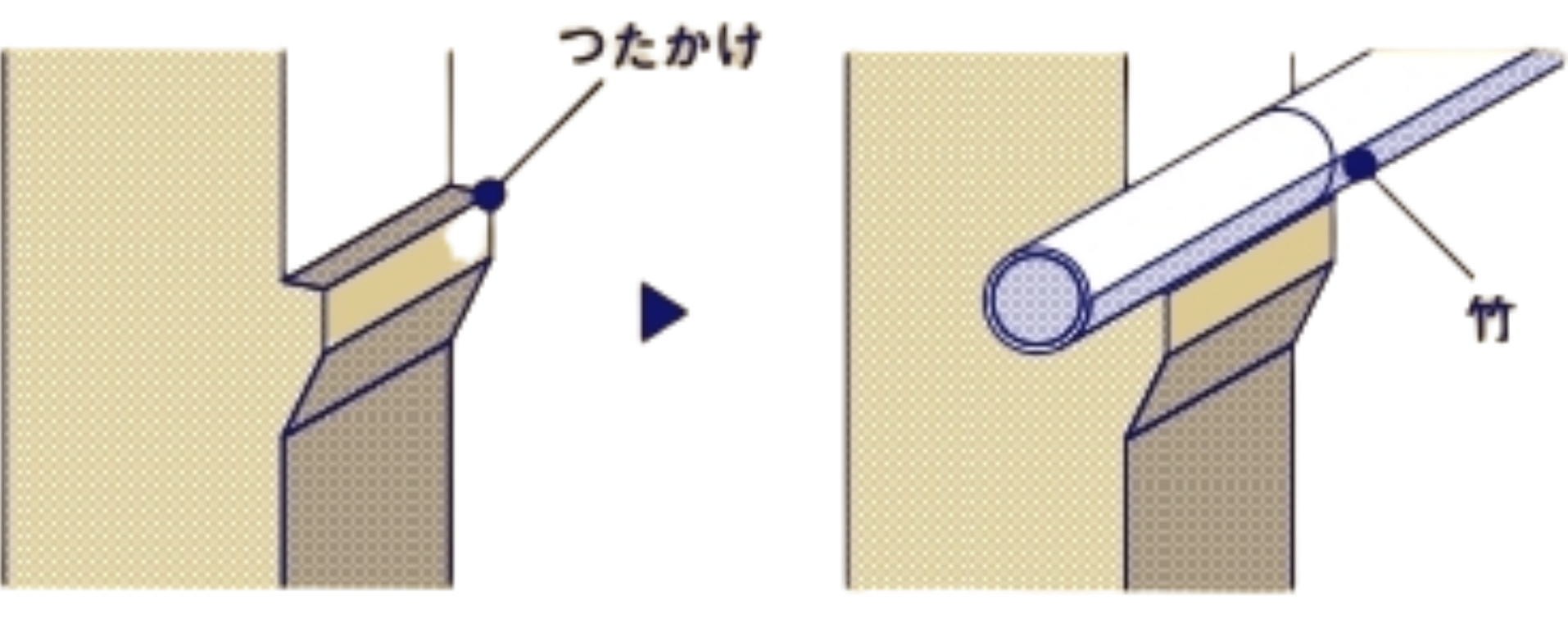

Tsutakake

“Tsutakake” refers to the notching performed on the exterior of pillars in order to affix bamboo lathing which will serve as the substrate when building an earthen okabe wall. These notches in the pillars are used to hold the bamboo lathing in place, thereby eliminating the need for nails and reducing the weight that they would add and making it less likely that the earthen wall will collapse.

Plaster finish

The plaster used is either quicklime plaster, that uses limestone as its primary ingredient, or shell lime plaster, that uses shell lime from shells as its primary ingredient.

Plastering seen around Tomo

In Tomo, limestone-based plaster is used. Limestone plaster is made by extracting starches and fibers from chondrus and funori seaweed and adding this to slaked lime.

In Tomo you will find gray plaster which has been colored by the addition of ink made from burnt pine, and you will find yellow “kiotsu” walls made by adding oyster shell ash and fibers to yellow clay.

白漆喰

白漆喰と灰漆喰の建築物

灰漆喰

黄大津

瓦

Roofing Techniques

All of the town houses in Tomo have tile roofs. The tiles used in Tomo are called “ibushi-gawara” (smoked tiles), which are fired without being glazed, and they come mainly from the Kikuma and Sanuki regions of Shikoku.

Tiling seen around Tomo

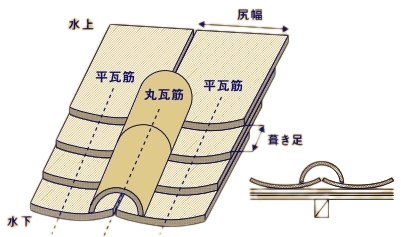

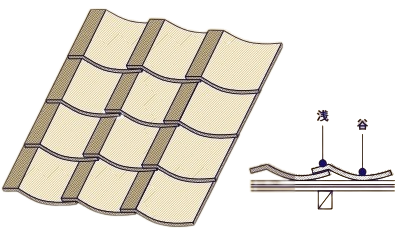

There are two types of tiles found in Tomo: “hon-gawara” formal tiles and “san-gawara” pantiles. The dimensions of these tiles vary based on era and potter.

In Tomo…

Old tiles are another of the materials that get reused in Tomo; hence, the same building may often have tiles of different shapes and sizes.

Hon-gawara tiles

Hon-gawara tile roofs have a longer history of use in Tomo, while san-gawara tiles came into use gradually from the end of the Meiji period.

San-gawara tiles

Old san-gawara tiles are called “shinogi-tsuki” (ridged) san-gawara because of the pointed, triangular shape they form when heaped up.

金物

Metalworking Techniques

Buildings constructed in the Edo and Meiji periods use “wakugi,” the old, traditional nails used in Japan. Long ago these nails were used in the construction of shrines, temples and all sorts of buildings, including the Golden Pavilion of Horyuji Temple. Unlike the Western-style nails commonly used now, which have a rounded profile, wakugi have a square profile and were fashioned one at a time. Their appearance resembles that of the nails used in the making of wooden boats.

Tomo has long been home to a thriving iron and steel industry producing “funekugi” (boat nails) and various other metal products. It is likely that wakugi nails, iron clamps and other metal construction materials were manufactured in Tomo.

Visit the Tomonoura Folk Heritage Museum in Fukuyama City to find out more about Tomo blacksmiths.

耐震

Earthquake-proofing

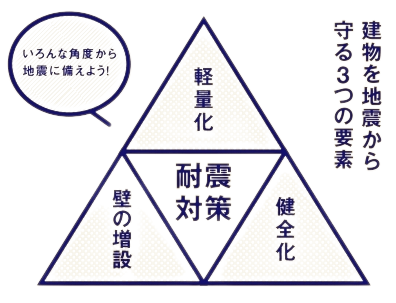

While the old appearance of the buildings within the Preservation District for Groups of Traditional Buildings must be maintained, it is also essential that they be protected against earthquakes. Unlike modern buildings, old buildings do not resist shaking during earthquakes but, instead, are deformed slightly by it, thereby absorbing the force of the earthquake and preventing collapse. When earthquake-proofing these buildings, it is important to understand this difference in thinking.

Building restoration

As historic buildings age they undergo weathering, termite damage and other sorts of deterioration in their structural pillars and beams, exterior walls, roof, etc. Replacing these damaged materials and restoring the structure to a sound state is the first step taken during the earthquake-proofing process.

Roof lightening

The tiled roofs of old buildings used earth underneath the tiles in order to achieve the desired gradient and overall appearance. As a result, the upper part of these buildings is extremely heavy, creating a fragile balance that can easily cause the building to collapse in an earthquake. Removing the earth under the tiles is therefore done to improve these buildings’ resistance to earthquakes.

Adding and enhancing walls

In addition to keeping out wind and rain and creating privacy, the walls in buildings help to prevent collapse during an earthquake by increasing a building’s capacity to resist lateral force. Thus, adding and enhancing walls is an extremely effective way of improving earthquake resistance.

Three essential elements for protecting buildings from earthquakes

Protect against earthquakes from all angles!