Cultural properties that tell the history of the town

Points of Note in Tomonoura

Symbol of Tomo built as a navigation guide

Jōyatō Stone Lighthouse

The Jōyatō stone lighthouse (also known as the Toroto lantern) is a symbol of Tomo as a port town which has been shaped by the “turning of the tide.” Built in 1859, its light has guided ships into and out of Tomo’s port. From its foundation stone to the spherical stone at its top, the Jōyatō stone lighthouse is 5.7m tall, while the platform on which it sits is 3.4m tall. If measured from the very bottom of its supporting masonry, this giant stone lantern is over 10m in length, making it one of the largest Edo period night-lights still in existence.

Stone steps connecting the land and sea

Gangi

The Gangi is a stair step landing connecting land and sea which was built to make it possible to load and unload ships at any time, regardless of the tide. Stretching approximately 150m in total length and featuring as many as 24 stone steps at its widest point, the Gangi runs all around Tomo’s port and is one of the largest stone structures in Japan. Built in 1811, the Gangi stone steps are still used today as a boat landing.

Jetty protecting the port from storm waves

Hato

A jetty, called a “hato” in Japanese, is a structure which extends out from shore and is used to protect ships from typhoons and other strong winds and high waves. There are three jetties around the port in Tomo: one on the eastern side which extends from Daigashima Island, a second on the western side which extends from Yodohime Shrine, and a third on the southern side which extends from Tamatsushima Island. All three are from the Edo period and are among the largest stone jetties found in Japan. The view of the port from out at sea atop the jetty is one of the must-see sights for any visitor to Tomo.

Site used to keep watch over the sea and town

Funabansho Remains

Also known as the “Tomibansho,” this building was used as both a lookout for spotting suspicious or dangerous ships as well as an administrative sight for managing safe passage into and out of the port. During the Edo period, a stone wall was built atop a hill at the base of the jetty, and the Funabansho was then built atop that. The current building is not the original; however, the stone wall and stone steps beneath it are from the Edo period. The nearby bell tower was used to signal the hour as well as to alert people in case of emergency.

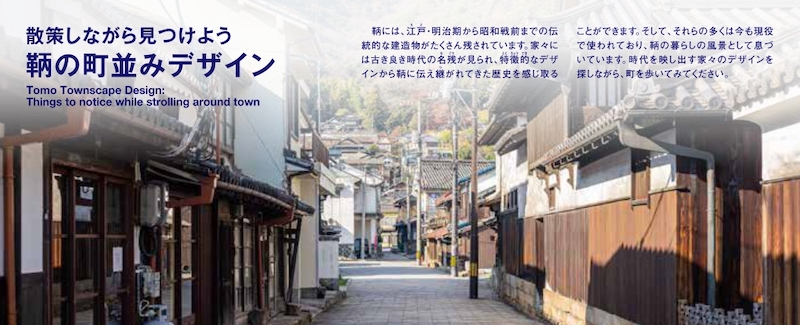

Historic Edo period townscape

Tomo-chō, Fukuyama City Preservation District for Groups of

Traditional Buildings

*Important Preservation District for Groups of Traditional Buildings

This area features a collection of traditional merchant homes, temples, shrines, stone walls and structures, port facilities and other architecture built between the Edo period and the 1950s. Narrow row-houses connected one to another at the eaves, spacious residences of wealthy merchants, cramped roads and alleyways that open out onto the sea…as you walk around you feel as if you have slipped back in time to a port town of long ago.

Preserving a successful merchant’s life and livelihood

Ōta Residence *Important Cultural Property

The Ōta Residence, home to a shipping family of the Meiji period, preserves the residence and storehouses of a wealthy merchant who prospered in the Hōmeishu medicinal liqueur brewing and sales business of the middle and late Edo period. The main home is surrounded by Hōmeishu medicinal liqueur storehouses, all kept just as they looked in their heyday. The design, which incorporates namako-style walls and checkered earthen floors, the exquisitely fashioned wickerwork ceilings hung with rattan blinds, the stair-step chest of drawers, the mairado-style wooden doors…this house is filled with fashionable details typical of a wealthy merchant’s home in the Seto Inland Sea area.

A stately waterfront building

Chōsōtei of the Ōta Residence *Important Cultural Property

This building sits just behind the Jōyatō stone lighthouse, looking out on the port and bordered by a white wall atop a stone wall. This stately townhouse has at various times served as a guest house for feudal lords and even the members of the Ryukyuan mission to Edo. The seven court nobles, including Sanjo Sanetomi, who were exiled from Kyoto in 1863 stayed here on their return to Kyoto the following year; as a result, it was designated as a historical site (the “Tomoshichikyoochi-iseki” [lit. “Tomo seven court nobles historical site”]) by Hiroshima Prefecture.

Tracing Sakamoto Ryoma’s footsteps in Tomo

Iroha Maru Museum *Tangible Cultural Property

This is a white wall of the “Hamagura” from the end of the Edo period. Today, it is a museum which traces the journey of the Iroha Maru, a ship belonging to the Kaientai trading company of Sakamoto Ryoma, which sank in an accident offshore of Tomo in 1867. Because of this accident, Sakamoto Ryoma and his group stayed in Tomo while negotiating compensation for the accident, but he had to keep a low profile, residing in secret in a room on the second floor of the house of Masuya Seiemon, which is reproduced in the museum.

A typical Edo period merchant’s house

Tomonotsu Merchant House *Important Cultural Property

The main building is an Edo period merchant’s house with earthen floors and a narrow frontage, while the adjoining storehouse was built in the Meiji period. The road in front of the house was sharply inclined, making it difficult to access with a cart. The current structure appears to be held up by concrete walls, but the concrete walls were placed at the time that the road was leveled, thus showing the original height of the road.

Japan’s only sectional stage with a connection to feudal lord Toyotomi Hideyoshi

Nunakuma-jinja Shrine Noh Stage *Important Cultural Property

It is said that this sectional stage was built by the Noh-loving feudal lord Toyotomi Hideyoshi for his soldiers. After Fushimi Castle in Kyoto was abandoned, the second shogun, Tokugawa Hidetada, passed the stage on to Mizuno Katsunari, lord of Fukuyama Castle. Then, in 1650, it was gifted to Gionsha (now Nunakuma-jinja Shrine). It has a permanent shingled roof, dressing room, mirror room and covered bridge passageway, and it is still used today to stage Noh performances.

Votive offerings for safety at sea

Stonework at Nunakuma-jinja Shrine

*Important Cultural Property (Torii gate) / (Stone lantern)

Worshipers visit Watasu-jinja Shrine to pray for safety at sea and Gionsha to pray for good health. There is an abundance of things to see here, from the unique “torii-busuma” torii gate that looks as if birds are perched on its top beam, to a fence around the shrine engraved with Edo period ship names, among others, a 3.24m tall stone lantern dedicated by Mizuno Katsusada, third lord of Fukuyama Domain, which is inscribed with the word “Keian 4 (1651),” stone guardian dogs and much more.

A long stairway leading to a spot perfect for looking out over all of Tomo Bay

Iō-ji Temple

It is said that this temple was established by the Buddhist monk Kukai (known posthumously as Kōbō Daishi) in 826 and, given its location halfway up the mountains behind the Tomo port, it came to be used as a navigational guide by arriving ships. The sound of the temple bell echoes all the way to the port. The principal image of the Buddha in the temple, a standing wooden statue of Yakushi Nyorai (Important Cultural Property), is said to have been fashioned in the middle of the Muromachi period. It is shown to the public only once every six years, so hopefully you will get lucky with the timing of your visit!

A row of temples lined up to protect this castle town

Teramachi-suji Street

Tomo is home to 19 temples and dozens of shrines; so, it is said that you cannot go anywhere in town without bumping into a temple or a shrine. Teramachi-suji Street on the northern side of the town has a particularly dense collection of temples. In the early years of the Edo period, Fukushima Masanori used temples as fortifications, which is why the development of this castle town features so many temples along the northern side of the castle. Many of these temples also served as temporary lodging for the emissaries of the Joseon missions to Japan.

A divine eye watching over the people of Hira district below

Yodohime-jinja Shrine

Situated at the top of a hill like a guardian protecting the entrance to Tomo’s port, the chigi (ornamental crossbeams on the gable of a Shinto shrine) atop the shrine’s roof are a striking sight visible from the sea. The shrine’s annual summer ritual features portable mikoshi shrines being whirled about to the rhythm of taiko drums and accompanying music so energetically that it appears that they are about to be hurled, thus giving rise to the name “Hira-no-Nage-Mikoshi” (lit. “hurled mikoshi of Hira (the name of the local region)). Another name for the festivities is “Hira-no-Dango-Matsuri,” because local residents prepare special festive dango-style dumplings to give to their relatives.

Picturesque scenery which charmed even the Joseon missions to Japan and others from overseas

Tomo Park *Place of Scenic Beauty

Together with Miyajima Island, this site was designated as a park by Hiroshima Prefecture in 1873, and in 1925 it was designated as a Place of Scenic Beauty by the national government. Sensuijima Island located in the center of Tomo park features a walking path and observation platform, and, along the walking path, you will find geological layers and rocks that date back to the Mesozoic and Cretaceous eras of the dinosaurs. The combination of calm, sparkling blue waters and prominent island ridges creates strikingly beautiful scenery, even compared to the other beauty of the Seto Inland Sea.

Guest house for senior emissaries of the Joseon missions to Japan

Joseon Mission Historic Site on the Tomo Fukuzenji Temple Grounds *Historic Site

Built atop a hill, Fukuzenji Temple is a venerable temple which dates back to the Heian period. It was used as a guest house for the emissaries of the Joseon missions to Japan. One of the emissaries,Yi Bang-eon, in 1711, wrote in a book Nitto Diichi Keisho that the scenic view from Fukuzenji was the most beautiful of anywhere between Tsushima and Edo, and a stone monument inscribed with these words can be found at the temple today. In 1748, Gye-hui Hong, the head officer of the envoy, named the guest hall “Taichoro” (lit. “hall facing the tide).

A wealthy merchant’s tower gate overlooking the islands in the sea of Tomo

Taisensuirō

This tower gate was built by Osakaya, a wealthy merchant house in Tomo. The reception room on the second floor offers visitors a fantastic view of the islands of Bentenjima and Sensuijima. The name “Taisensuirō” (lit. “hall facing Sensui”) was given by the Edo period historian Rai San’yō because of this view. The view from this tower gate is referred to as “sanshi-suimei” (lit. “purple mountains and glistening waters”).

Vermilion-lacquered temple hall atop a cliff

Bandai-ji Temple Kannon-dō Hall (Abuto Kannon)

*Important Cultural Property

Situated atop a cliff, this temple hall overlooks a vast panorama of islands and sparkling blue seas. Among those who have captured this scenery in their artwork was the ukiyo-e artist Utagawa Hiroshige. Because of its prominence, the temple hall was once used as a navigation guide by sailors. Long ago people would come here to pray for safety on the seas, but now it is a well-known destination for those praying for safe childbirth; thus, one wall of the Kannon-dō Hall is lined with votive tablets depicting breasts.

A traditional fishing method going back 300 years

“Tai Shibari Ami” Net Fishing Technique *Intangible Folk Cultural Property

Six boats venture out into the offing searching for schools of sea bream. Two boats spread a huge net and then cross paths in order to close it around the sea bream and haul them up quickly. Tomo is the only place in Japan where this traditional fishing method is still practiced and, in order to keep it alive, Tourism Sea Bream Net-fishing has been held at the start of summer every year as a longstanding tradition in Tomonoura since 1923.

A major event to announce both the end of spring and the start of summer

Fukuyama Tomonoura Bentenjima Fireworks Festival

This annual fireworks festival has been held since the Edo period in order to pray for safety on the seas; among other sources, an 1831 entry in the Nakamura-ke Diary mentions the “Benzaiten Fireworks Festival.” On the day of the festival, the prefectural road becomes a car free zone which is lined with stalls offering cotton candy, candy apples, yo-yo fishing and other enticements amidst a bustling, festive atmosphere. A traditional performance of “aiya-bushi” starts everything off before being followed by a display featuring some 2,000 fireworks.

Loosing arrows to expel evil spirits and pray for a year of tranquility and peace

“Oyumi Shinji” Shinto Ritual *Intangible Folk Cultural Property

Archers wearing medieval eboshi hats and ceremonial suo garb pray for a new year of peace and tranquility by carefully aiming and loosing their arrows at targets. The arrows are fired at targets painted in characters meaning “equality.” Designated town participants parade around crying out, “Speak, speak!” It is a longstanding midwinter tradition in Tomonoura intended to celebrate the lunar New Year. This annual ritual is held at the Hachiman-jinja Shrine on the grounds of the Nunakuma-jinja Shrine.

A summer fire festival featuring giant, blazing red pine torches

“Otebi Shinji” Shinto Ritual *Intangible Folk Cultural Property

“Otebi” are giant, 4.5 m long pine torches that weigh in excess of 200 kg. Three such fiercely burning torches are carried by the faithful, drenched in water from the head down, slowly but surely up the stone steps of Nunakuma-jinja Shrine. Once the otebi reach the worship hall, they are then loaded onto portable mikoshi shrines and carried around town as a purifying fire with which to beseech the gods for safety on the sea and good health.

Celebrating children’s growth with a large wooden horse parade around town

Hassaku no Uma-dashi

A large white, wooden horse is pulled around town atop a wheeled platform on which children also ride. Although this traditional event has been celebrated in Japan since the Edo period, it is now found only in the town of Tomo. The event has featured processions of Hassaku no Uma from the Edo period to the present, both large and small, parading slowly through town, giving a thoroughly charming and historical atmosphere distinctive to Tomo.

Parading chosai floats to pray for peaceful sea travel

Aki-matsuri (Autumn Festival at Watasu-jinja Shrine)

This annual autumn festival is held at Watasu-jinja Shrine on the grounds of Nunakuma-jinja Shrine. The enshrined deity is Ōwatatsumi-no-mikoto, a god of the sea. It is an energetic, three-day festival with the first day featuring the sacred mikoshi-togyo procession, the second day featuring the Otabisho-sai Festival, and the third day featuring the Kangyo-sai Festival as the procession returns to the shrine. As the chōsai floats parade through the town, the townspeople welcome them with decorated eaves, paper lanterns with umbrellas, curtains, pine decorations, picture lanterns and other impressive decorations.

Inscribed names of dock workers who proved themselves in tests of strength

Tomonotsu Chikaraishi Strength-testing Stones *Tangible Folk Cultural Property

Shipping has always been a major part of Tomo’s identity, and this has included lots of dock workers responsible for loading and unloading ships. At festivals and other events, these dock workers would engage one another in strength contests involving the carrying of heavy stones. At the Nunakuma-jinja and Sumiyoshi-jinja shrines can be found offerings of the stones that were carried, with the weight of the stone and names of those who carried it inscribed upon each. Among these are stones weighing more than 200 kg, which shows how surprisingly strong some of these dock workers were.

An unbroken tradition of medicinal alcohol dating back to the Edo period

Hōmeishu Medicinal Liqueur

Hōmeishu medicinal liqueur in Tomonoura is said to have begun with Kichibe Nakamura, a specialist in Chinese medicine who arrived here from Osaka in 1659. It became a vital industry of Fukuyama Domain, contributing significantly to the domain’s finances, and its status was reflected in the fact that hōmeishu was given as a gift to Commodore Perry when he visited. The method of preparation involves combining 13 herbs with mochi rice, malted rice and shochu liquor, and there are four places where this traditional preparation method is still practiced today. There are even sweets which incorporate hōmeishu.

Savor the taste of sea bream from the Seto Inland Sea

Sea Bream Dishes

Given its well-known association with sea bream net-fishing, Tomo has its own, distinctive sea bream-based cuisine. No celebration is complete without tasty “sea bream somen” noodles made with sea bream soup stock and its meat in it. Tomo is filled with restaurants offering sea bream cuisine, including “tai-meshi” (rice cooked with sea bream), “tai-chazuke” (a dish made from rice, tea and sea bream), “kabuto-ni” (a dish which includes simmered sea bream heads) and much more. For anyone wanting to experience Tomo’s gourmet offerings, these dishes are not to be missed.

A crunchy texture that will leave you hooked after just one bite

Nebuto Karaage

When people think of the Seto Inland Sea they often think of the small fish known as “nebuto (official name is tenjikudai),” (“Indian perch” in English) which is characterized by large, stone-like bones in its head. It is frequently cooked with the head removed and is a popular fish fry choice. It has a pleasant “snacking” texture that makes it a perfect finger food and accompaniment to alcohol. Nebuto is a staple of any izakaya-style pub menu in Fukuyama and is tremendously popular with young and old, men and women alike.

The concentrated flavor of delicious, small fish

Small Fish Paste Products (e.g., Gasuten)

Located in almost the very center of the Seto Inland Sea, Tomo is home to a thriving fish paste production industry that includes chikuwa, tempura and much more. Among these, one of the most well-known delicacies is “gasuten,” a paste product made from small fish. The name “gasuten” comes from a Japanese ideophone for crunchiness, “gasu-gasu,” which evokes the somewhat bony crunchiness that this product has due to it being made from nebuto and small fish that are ground up, bones and all. Every visitor should try this quintessential port town flavor.